“…wish day come…”

Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee;

Not untwist—slack they may be—these last strands of man

In me or, most weary, cry I can no more. I can;

Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

(Gerard Manley Hopkins, “Carrion Comfort”)

I’ve never been prone to despair–anger, fatigue, aggravation, depression, frustration, all these and more, but never despair, never that pervasive sense of hopelessness, which robs all strength and dims the vision. Even at the darkest moments, or so they seem in retrospect, in Camp Kue Army Hospital, Okinawa, during Christmas and New Year’s, 1967-68, sick unto death, surrounded by the detritus of war, by the “last strands” of young men worn down, eroded, dying around me–even in those moments, there was no despair. In the years since, pursuing a calling as a Christian minister and Veteran’s Hospital chaplain, I have watched as the world continued to wage the war that never ended, to borrow a phrase: Falklands, Grenada, Panama, Bosnia, Rwanda, South Africa, Rhodesia, Somalia, Kuwait, Iraq/Iran, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Israel, West Bank, Syria, Colombia, Peru, Chile, India/Pakistan, East Timor, the Philippines, Chechnya, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, now Iraq again and still Afghanistan, Sudan, Syria, Kurdistan. (Did I miss one, or two? See the Postscript at the end of his essay.) I’ve watched as “carrion comfort” seemed to be the special of the day, a monotonous and tedious serving of the same raw meat day after day, year in, year out. And, even then, I have not despaired, nor rarely come close to it.

Of late, however, as Israelis and Palestinians continue to have at each other in yet another mindless round of violence, as the daily toll in Iraq and Afghanistan mounts up, with no end in sight, I have begun to feel the inroads of despair, a sort of mind-numbing decision-less torpor, an ease with not having, or even wanting, to make moral decisions, in the face of an equally mind-numbing display of political rhetoric, a terrorization of the language, so to speak, when the language of moral discourse has become corrupted. I have come to mistrust all the lessons I learned in my history classes, the lessons history is supposed to teach us, that we are not supposed to repeat, lest we be doomed. It doesn’t seem, these days, that anyone has learned any lessons at all. If anything, it seems that most leaders of most nations are intent on repeating the worst mistakes of our collective pasts. I have had to rethink the heritage of my faith, to re-view what I have been taught about the role of the church in public affairs. (I am not so sanguine as to think that the church is, or ever has been, in any of its forms, possessed of infallibility.)

St. Augustine, in mulling over these questions, told the story of Alexander the Great, who was confronted by a pirate. The pirate, it was said, was a bold soul who told Alexander to his face that, from the moral point of view, their behaviors differed only in the scale of the consequences: Alexander attacked the foe for the profit of the state, the pirate for his private interests. Augustine concluded, “And so if justice is left out, what are kingdoms except great robber lands?”(The City of God, IV,4) To raise the question these days of justice and “the moral point of view” is difficult, at best, and risky, at worst. It smacks of moral majorities and minorities, of evangelical fervor. It has been co-opted by all parties, globally, in one form or another, as justification for a particular political or economic or religious agenda. Terms like “evil,” “satanic,” “criminal,” “horrific,” “terrorist/terrorism,” are now bandied about by anyone who happens to have an ideological or economic axe to grind. Our leaders have taken to issuing ultimatums and threats, to speaking in absolutes, rather than in the measured language of diplomacy. One of our Presidents once spoke to the leadership of Israel, publicly, as if they were a bunch of rowdy 10 year olds: “..and I meant what I said.” There is, or there was when I was a ten-year-old child, an implied threat in such a statement. (Did the President intend a threat, I wonder? And with what would he threaten Israel?) The moral confusion in our foreign policy in the Middle East is nothing short of terrifying. The politics of self-interest, absent justice, on all sides, has wreaked nothing but havoc.

“The moral point of view,” then, is a place to start. Alexander’s pirate would have us look at the nation state. I would have us look a bit more closely, a lot more closely, with greater particularity, at local consequences. The veterans I once served all bore the marks of having been fed on a steady diet of “carrion comfort.” In them, the scale of the consequences is fairly easy to see—broken bodies, wounded spirits, lost family, abandonment by their society, their lives nibbled away by budget cuts and bureaucratic violence. In them, the karma is present, astonishingly present, and painfully visible. In others, it is present, just not so obvious. My father, for instance, a WWII Navy veteran, who only near the end of his life, was able or willing to talk to his grandchildren about his six years on a destroyer, on North Atlantic convoy duty, at Guadalcanal, North Africa, Sicily, Iwo Jima; he bore the consequences all his life, some in body, most in spirit. He left home in 1939, a gifted amateur athlete with great expectations and returned six years later, his big league dreams but dust and ashes. My daughters have asked me, many times, “Daddy, why don’t you talk about what you did in the war?” How do I talk to them about the lovely young men I watched die, in the beds around me at that hospital on Okinawa, about that ruddy-cheeked young Army sergeant, in the bed next to me, whose R & R friends sneaked in a fifth of whiskey for him, who drank it all that long night and died as I watched in frozen-tongued horror? He sat on the edge of his hospital bed, back to me, in the glow of the hall light through our room door, and slowly, so slowly, tilted to his right, lay down and died. (Most of the young men in that hospital wanted me to tell them how to find the drugs they craved, once they learned I was stationed there. Alcohol, they knew how to find, because for soldiers, sailors, and marines, it was always plentiful, supplied at base clubs at cut-rate prices. Both alcohol and drugs rank high on the scale of consequences.) How do I make real to my children the awful “scale of the consequences?” How do I give them something that will save them and their children from the dogs of war? How do I help them “wish day come?” How do I make plain to them that the “profit of the state” will always come at the expense of that single person, that sergeant, their Grandfather, their Father, that veteran under the bridge whom they speak of as “homeless,” whom they do not “see” as one of the consequences.

It is easy, all too easy, to engage in moral discourse on the national and international level, to “watch the news,” as we say, disconnected in heart and spirit. It is much more difficult to speak the now degraded language of moral discourse in the face of the Other, that single person, widowed or orphaned on September 11, that mother in Bethlehem or Ramallah or Gaza or Tel Aviv or Netanya or Kabul or Baghdad, to face that raging anger, that uncomprehending puzzlement at what has been wrought on them.

One of my hospital patients, one of “my boys,” who was in his early eighties, was a Marine at one of the nastier amphibious landings in the Pacific war. The Navy bosun’s mate who drove his landing craft “chickened out” under heavy fire, as he puts it, and dumped his load of Marines in deep water. Most of them drowned, weighted down by their gear. He survived because he trod on bodies beneath him. He still dreams and cries aloud at night, and there is where the “scale of the consequences” needs to be measured, in the feel of a pack-laden back or shoulder or stomach beneath your feet, gasping and struggling for breath and life, knowing it means death for your best friend.

I have grandchildren now, bright as new pennies, filled with lovely hope. They awaken each morning “wishing day come.” I do not want them fed on “carrion comfort.” For that to happen means that I, and others, must begin to do the work of firm resolve, the proper work of the moral point of view, the hard work of hope. They need to know that there are human consequences, close to them, for what they see and hear on television, or what they will hear in their “current events” hour in social studies class. I will, in time, as they are ready, do that work with my children and grandchildren. I will tell them what it was like. I will not feast on despair, nor will I feed it to them. I will tell them that they “can something.” I will show them. By God’s grace, I hope you will, also.

Postcript: July 8, 2016: Since first written, the bodies have begun to pile up…Oklahoma City, Columbine, Newtown, Charleston, Paris, San Bernadino, Baltimore, Chicago, Orlando, Falcon Heights, Baton Rouge, Syria, Afghanistan again, Iraq again and again, Nigeria, Sudan, Dallas…and the language of public political discourse continues to coarsen.

In peace,

Ken Frazier

Fire and Ice

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

“The rain fell on the earth forty days and forty nights.” (Genesis 7:12)

“One does not appreciate the sight of earth until one has traveled through a flood…As we progress up the river, habitations become more frequent but are yet still miles apart. Nearly all of them are deserted, and the outhouses floated off. To add to the gloom, almost every living thing seems to have departed, and not a whistle of a bird nor the bark of the squirrel can be heard in this solitude. Sometimes a morose gar will throw his tail aloft and disappear in the river, but beyond this everything is quiet–the quiet of dissolution. Down the river floats now a neatly whitewashed henhouse, then a cluster of neatly split fence rails, or a door and a bloated carcass, solemnly guarded by a pair of buzzards, the only bird to be seen, which feast on the carcass as it bears them along. A picture frame in which there was a cheap lithograph of a soldier on horseback, as it floated on, told of some hearth invaded by the water and despoiled of this ornament.”

(Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi)

“Pray for peace and grace and spiritual food,

For wisdom and guidance, for all these are good,

But don’t forget the potatoes.”

(J. T. Pettee, from “Prayer and Potatoes,” in How to Cook a Wolf.)

Sharp Mountain, Georgia

On Miracles

Miracles do not always come easily, do not burst upon us with the holy light of revelation; they must sometimes be conjured from the sickly flame of despair, the hands held close to keep the draft away and the gaze steadfast, bringing to bear upon the matter the grace of faith, until through the dark of disaffection the small flame thrives, leaping at last to burn with a light that holds the very soul in thrall, by which I mean, my good friend, that one must not go limping home, must one, when all is wretchedness, no, one must sit here…

(Elleston Trevor, writing as “Adam Hall,” in Quiller Bamboo.)

Agriculture, Food, and Grace

by Ken Frazier

“Food probably has a very great influence on the condition of men. Wine exercises a more visible influence, food does it more slowly but perhaps just as surely. Who knows if a well-prepared soup was not responsible for the pneumatic pump or a poor one for a war?” (Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, The Waste Books.)

I thought I had gotten over all that childhood embarrassment long ago–sitting out in the open in Howard Johnson’s restaurants, on the road again somewhere in North Carolina or Tennessee, all of us with eyes scrunched tightly closed while Daddy offered thanks for our food, in a formula full of “thees” and “thous” and “heavenly Fathers” while my grilled cheese sandwich got cold, and my face warm–with embarrassment–and here I was, again, 45 years later, sitting out in the open in an Atlanta airport snackbar, in full view, with Mother and Daddy–he is still “Daddy” when he “offers thanks”–the three of us holding hands over a rickety snackbar table laden with the greasy fruits of fast food, saying thanks with “thees” and “thous” and “heavenly Fathers,” and me hearing all my friends and colleagues choking over the patriarchal language, while this time the fries got cold. (Actually, I don’t recall which particular fast food I had, but I do know it was one of the many eminently forgettable varieties of airport fast food. They all taste the same anyhow, and I have begun to suspect they all are made from the same basic substance, an unknown substance, shaped, flavored, textured and colored to look like chicken, tuna, ground beef, or potato, broiled, or deep fried in yesterday’s oil. Shades of “soylent green!”)

The “grace” my father said there in the Atlanta airport hadn’t changed any in 45 years, but sitting down to eat had changed, beyond recognition. 45 years ago, the notion of food being “fast” would have been as alien to all of us, waiting in restaurants and diners a decently reasonable time to be served the food we ordered, without a decent wash-up and sit-down, without some family chit-chat around the table, a chance to run the kids around the parking lot and burn off the pent-up road tension, a time to stretch the body and move the cramped muscles from travel position to eating position—such an idea would have been as foreign as would the notion of inclusive language to my father. (The body knew, I think, that it needed a gentle transition from one position to another. My wife’s West Tennessee farming family knew that, so they came in from the fields and rested up during the middle of the day, stretched the working muscles into shape for eating, before they ate their big midday meal, and took a long nap before returning to the fields. I rather imagine the earth, too, needed that midday respite, to let the sun bake a protective tan crust over the darker soil beneath, to give it time to rest, to ease the heat.) The “Automat,” introduced in 1902 by Horn & Hardart, served “real” food, delicious macaroni and cheese, baked beans, creamed spinach, etc.

But for my father, and for so many others, the great need was for a quiet time at a table when a grace could be said that wasn’t fast, a time when the basic connections of the created order could be maintained, the switches reset, so to speak, the conduits cleaned and straightened, when the graceful flow between God and Creation could be acknowledged and furthered. Or, as I suspect was the case for my father and others, a time was needed when the faithful obedience of the human part of creation could be expressed in gratitude for some of the non-human parts of Creation. Duty and obligation were essential in maintaining a proper balance between the Creator and Creation. We creatures had to acknowledge, in every way possible, the beneficence of the Creator. The food we ate, by my father’s lights, was truly a gift of God. On the road, at home, visiting relatives and church friends as we did frequently–wherever we sat at table, indoors or outdoors, full meal or simple snack, a prayer of thanksgiving was always offered.

Eating, then, was always a religious act, and no matter how far I strayed in adulthood from those regular practices of childhood, there was always the sharp awareness that I “ought” to be offering thanks whenever and wherever I ate. (I must confess to something: I had to be reminded, rather sharply, at one of my daughters’ weddings that I had not “given thanks.”. I could have plead the noisy room, but no excuses will suffice.) Food was a gift of God. The earth which bore the food was a gift of God, fitting for our needs. It was never something which just “happened to be there.” There was no element of accident and certainly no element of chance in the marvelous taste of a tomato picked hot off the plant in mid-August, rinsed off, sliced, salted, and eaten then and there. God made the world and us, so that the tomato would taste that way. Certain things tasted good, and the body’s delight in what was good for it was God’s knowledge, not a happenstance, not a fluke of nature. Saying thanks had something to do with making the food appreciate the person who ate it.

# # #

The Platonic Tomato

Tomatoes have become perfect, the epitome of the Platonic ideal applied to the fruits of nature. Our tomatoes, the ones we picked hot off the vine in mid-August, and ate with a salt shaker in hand, were lumpy, misshapen, veined with deep brown grooves, asymmetrical, sometimes with bird-pecked and sun-healed wounds, no two the same size or shape. We never knew what they would look like when they were planted in the spring, nor even whether we would have a decent tomato come mid-summer. Too much rain, or too little, too much sun, too many bugs one year, and the crop would be slender. The gracefulness, the unpredictable gracefulness of weather, gave us a rich bounty, a diverse tomato harvest, all the more delightful in its surprising appearance, in its sheer unpredictability.

Now, the tomato is perfect, engineered to withstand all weather and all bugs, genetically manipulated to be uniform in color, size, and shape, and flavor. The tomato of today’s supermarket is the Platonic ideal, the perfect tomato, devoid of the diversity of grace, and so devoid of body pleasure. The perfect tomato can be seen any day of the week, any season of the year, in any grocery store produce section, stacked neatly, boxed symmetrically, same size and shape and color, a bright and even “tomato” red, world without end, and same bland flavor. In the world of ideal forms, there is A TOMATO. All the lumpy, ridged, frilled tomatoes of the Incas, and all their descendants, are manifestations of that ideal tomato. Now, in fact, we have, at hand, purchasable for a few cents, the actual ideal tomato, the realization of Plato’s dream.

# # #

Food, in our Southern eating, was always comforting, occasionally challenging, frequently exciting, varied and plentiful, always an occasion for gratitude, even if the prayers were said meal-in and meal-out by rote. This understanding of food as a source of grace was not restricted to the family table. I recall with deep nostalgia the foods prepared and served in the grade school cafeteria in Asheboro, North Carolina. To the best of my recollection, all the meats, vegetables and baked goods, save sliced bread and dairy products, were prepared from scratch in the school kitchens. The meals were rich and varied, marked by fresh vegetables in season, and the folks who prepared them would have walked off their jobs had they been asked to serve the swill that passes for a meal in our public school systems today. I have eaten school lunches with my granddaughter and have been appalled. (My eight year old granddaughter had to endure the ridicule of her schoolmates, at times, because she liked to prepare snacks to take to school that didn’t fit the usual school party snack paradigm. Her parents taught her how to prepare stuffed mushrooms, which she loves, so she took a Tupperware container of stuffed mushrooms instead of sugar-laden cookies and brownies.) Homeless shelters serve better food than what is served in our public schools, and it is often food obtained through donations or FoodShare, on a tight budget. (And do we think the students in our public schools do not know what we are saying we think about them by the meals we serve them? Do we honestly believe they do not understand the message we are sending?) We could always go back for seconds, as long as they held out, and on a day when “extras” were cooked, and that was often, we could get a small paper bag full–big crisp-on-the-outside and toothsome-on-the-inside homefries, genuine crispy rich pigskins (not these little dried up pieces of brown tough styrofoam in a bag, but real reddish-brown crisp and meaty pigskin pieces, cut off and deep-fried just minutes before, from the day’s ham), corn on the cob chunks, green beans cooked down in bacon grease, turnip greens with nice little pieces of ham swimming in the pot likker, pinto beans so rich and hearty you could live on them, with cornbread, for days. (My late father-in-law, a sawmiller and journeyman electrician, carried his quart jar of pinto beans, cornbread, and a fresh onion to work as his staple lunch nearly every day for years. I still remember, with deep nostalgia, that mouth-watering aroma when he opened the jar and sliced the onion. When I worked for him in the summer months, and we ate lunch together, he would watch me open my lunch box, take a look at my peanut butter and jelly or cheese sandwich, grin, and pass the pintos.) And, lest we turn up our noses at the high fat content of the meals that were served in schools and in homes, we need to remember that youthful obesity did not exist, not as a widespread and alarming phenomenon, as it does now.

For all of us, then, eating was, in one way or another, a religious act. It partook of the basic verities—grace, gratitude, humility, hospitality, sustenance, delight. And, since eating was a religious act and food was one of the basic sacraments, there was a moral dimension to food and eating. There were ethical aspects to all that. They may not always have been brought out into the open, but they were there and have begun to emerge in our time. We once practiced “pounding,” and my family was the recipient of a loving “pounding” on more than one occasion. A pound of flour, a pound of sugar, a mess of fresh-picked green beans, a pound of salt, a pound of dried beans, a pound of cake, canned goods, a ham or chicken, bacon, a bag of potatoes—all boxed up and delivered to the home of the newly-arrived, or the laid-off millhand, or the widowed, or the sick—the “pounding” was the direct expression of the ethical considerations of the goodness and abundance of the created order. It was, as was said, our “bounden duty.”

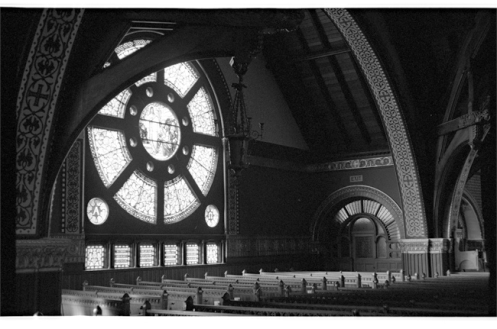

One of my favorite images.

On my way from Jasper to Pigeon Forge, through the heart of the Smoky Mountains. A panorama, composed from 5 different exposures.